. Mala is derived from the Sanskrit

, which means wrestler. They are one of the dominant

.

Malas constitute a total of 41.6 percent (5,139,305) of the scheduled

caste population of the state. They are largely concentrated in the

region. During the Adi-Andhra movement of the 1930s, several Mala caste

people, including few Madigas, especially from coastal Andhra called

themselves as 'Adi-Andhra' and were recorded in the census with the

'Adi-Andhra' caste name akin to

of Tamil Nadu. (Adi-Andhra is synonym word instead of using MALA or

Madiga, in Adi-Andhra Malas are 90% and 10% belonged to Madiga caste).

In the ancient times, Malas were mostly village watchmen or hardworking

laborers. They were skilled workers too and were also recruited by the

British Army because of their martial skills. Presently they don't have a

specific caste profession and can be seen in many professions.

.

history, culture and tradition. Mala's played a vital role in expansion of Kakatiyan kingdom.

military Malas are used to be called as Mohari (Telugu: mohari), the

street which they lived is known as "Mohariwada". The warrior

Yugandarudu who was the army chief of

is a Mala.

or Malas seemed to have hailed primarily from the drier upland areas

like the Deccan plateau. According to researchers like Ambedkar, the

Mahars and similar communities like Malas were actually warriors of some

defeated kingdom, they were pushed down in social status,they were

disarmed but retained as village servants.

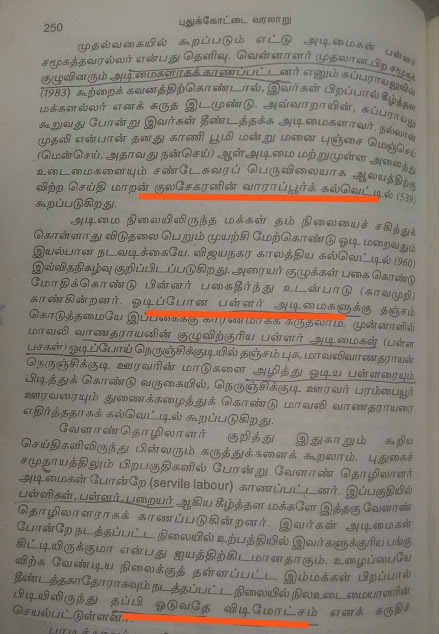

Mala caste has got prominence during the period of Palanati Bramha

Naidu (Prime Minister to Nalagam King of Macherla) (1170 to 1180 AD).

The Mala Warrior Mala Kannamadasu was the first Senapathi in the history

along with Kammas, Velamas and Reddies in those days. He was given high

regard by Palanati Bramha Naidu, since then Macherla Chennakesava swamy

became Kuladaivam to Malas in the Palnadu area.

Like all castes in India, today they generally believe in prestigious origins (see

). One such theory speculates that Mala or Malla (not the same as the family name Malla) is derived from

to know more). It should be noted that the word Mala in

means a mountain.

According to the story by Gurram Malla; Mala's are the descendants of Mala Chennappa, the son of Lord Shiva.

As a community they believe at some point they were independent

people not subject to any caste restrictions and resent the present

condition as unfair. Thus, unlike many other Dalit communities, they are

not resigned to their

which is a requirement for caste control along with social violence.

There is a strong ethnic, cultural and linguistic relation with

-similar to MALA community of Tamil Nadu and Kerala, Karnataka states as well.

.

And it has been pointed earlier, some of them were employed village

messengers (Maskoori or Elodu) and some as watchmen of the village

chavadi by the middle of Twentieth century. Malas were also employed to

dig graves. Malas employed to see the irrigation in villages called

Neerati, Neeradu. Mala women were skilled in basket making.

There were kin-communities of Malas such as Baindla, Pambala, Jangam,

Poturaju, Mashti, Mala dasari / Mala Dasu / Mithaalayyalavalu, Dandems,

or Mala sale, Mala Jangama.

Mala Dasari/Mala Dasu has been a tradition of Tamil Nadu, which spread

over to Andhra Pradesh between 9th and 10th century. Regarding Mala

dasari caste a mention was made by Emperor Shri Krishna Devaraya in his

15th century book

OR VISHNUCHITTIAM OR MALA

DASARULA KATHA. Further, Sri Krishna Devaraya mentioned that Malas were

bandits along with Boya community, that was the reason why Malas in

later period were appointed as Kavalivaru or Talavari to prevent thefts

and bandits in village. Baindlas were priests assisting at Mala

festivals and sometimes at sacrifices for the whole village when

epidemics like cholera visit the village. They were also experts in the

art of

.

like Yanthra, Manthra, Thanthra and they played major role in village

goddess jataras. Pambala people are very skillful in singing songs of

tribal goddesses by playing a musical instrument called

.

called Boddu Rai a stone which symbolic to a village protecting goddess

is a heavy process maintained by Pambala priests. A senior pambala

priest cuts the sheep neck with his teeths and kills it. This is called

as "Gou pattadam". The blood of the dead sheep collects in to a basin

and mix with a heavy amount of rice and by using the rice they draw a

line around the village borders called "Poli challadam". They build the

Bodrai and completes the Pooja, Balulu, etc.

Few years ago the Hindu Brahman pujaris (Ayyagarlu, Priests)

hesitated to attend Mala marriages, children naming ceremonies and other

functions in Mala people homes. At that time Pambala people have done

the job of the Brahman Pojaaries. In villages, Pambala people know Sidda

Vaidyam or Pasaru Vidhyam a process of using raw medicinal plants in

curing people and animals.

Jangams were traveling priests begging from Malas and at night they

were to keep vigilance at the graveyards. Poturajus were another group

of priests serving the village spirits both benevolent and malevolent.

They also assist the priestess when the sacrifices were offered. Mashtis

were traveling acrobats performing their heroics at the outskirts of

the villages where caste villagers turn up to watch them. Mala dasoos

were another set of priests who reside with Mala settlements. Dandems

were agricultural laborers either hired or bought by landlords.

used to weave cloths. The word (Telugu:"Netha") means weaving cloths.

In old Hindu religion the weavers who we called as Sale or Shali or

Padmashali, Chowdary and the tailors Mera or Merugu people hesitate to

weave or sell or stitch cloths.

instead. They are prominent in the

(CSI). They have made very good use of the Christian educational

programs, considerably elevating their social position and now form part

of the upper middle c lass. These highly educated, talented, motivated,

Christian Malas are commonly called

basin. They are not considered

by the Government of India but fall under the "BC-C" category (Backward

castes C-category) with 1% Reservation at state level and at national

level they come under

They have been demanding central Government to accord them SC status on

par with Dalit Buddhists, Dalit Sikhs and not to discriminate them on

religious grounds for being

. The case is pending with supreme court since 2005 when it was filed on behalf of

).

However, Christians never agreed that there is caste system in

Christianity but asking for reservations for SC Christians (a double

standard).

Christian malas believe in one god, equality in human race, and dont

under estimate or over estimate some one. moreover they play a major

role in politics externally. christians are 1% in India according to the

statistics but there is an estimated vote bank of 14%. which mean

christans could not able to come out due to the loss of reservation.

there is an evidential proof in the society that Mala christians are

more developed financially, socially and intellectually. communication

through the church played a vital role in developing the socially under

determined. Mala Christians dont believe that they are Malas, they

believe they are "son of god". they commonly say Classification is in

Hinduism and in Christianity everyone are son of god.

Former Chief Minister Chandra Babu Naidu, from 1996 to 1997, formed

the Justice Ramachandra Raju Commission to study categorisation among

scheduled castes. The commission's findings would eventually form the

basis for the A.P. Scheduled Castes (Rationalisation of Reservation)

Act, 2000, categorizing the fifteen percent reservation quota into four

subgroups (designated "A", "B", "C" and "D"; "B" and "C" represent

Madigas and Malas, respectively). The sub-categorisation policy was

implemented for a four-year period (2000–2004). The act, however, was

first challenged by {main petitioner WPNO.11472/97} the United Forum of

All Scheduled Castes, represented by that organisation's state general

secretary, Dasari Srinivas.V (Present DIRECTOR, AMBEDKAR STUDY CIRCLE,

SR NAGAR, HYDERABAD-38, 9397677681)and Dr.EV Chinnayya in

WPNo.21096/1996 mainly Challenged the Justice Ramachandra Raju

Commission validity under the constitutional provisions.

On SC's categorisation National Commission for SC,ST,` New Delhi,

called for discussions and fact findings were held from 7-7-1998 to

15-7-1998. At that time renowned and eminent Sr Parliamentarian Shri H

Hanumanthappa (Sr.Advocate in Supreme Court) was the Chairman and Shri

Bommidala Yadaiah (Telengana Mala) was also a Member in the National

SC,ST Commission. On 7-7-1998 Shri

hearings were noted by the commission on behalf of MRPS(Madiaga Reservation Porata Samithi) and Madiga Community.

On 9-7-98 the National commission for SC,ST has officially invited

Shri Dasari Srinivas.V ,State General Secretary,UFASC,AP, as he was the

main petitioner in the case to present his case on behalf of the MALA

community. 0n 10th July 1998 Shri Mallela Venkata Rao another leader in

Malamahanadu and on 11th July 1998 Shri PV RAO, President, Mala Mahanadu

gave the stand on categorisation.

A.P.Scheduled Castes(Rationalisation of Reservation) Act, 2000 was vehemantly opposed by malas and

has challenged the Act in Supreme Court saying that it is against the

Constitutional principles, which viewed SC's as a holistic single social

group. Supreme Court on 5 Nov 2005 has struck down the Act and the

verdict went in favour of

.

" The apex court pronounced its Judgement stating that State Government

has no power to sub-categorize Scheduled castes into groups to

implement reservations in the field of education and employment in

exercise of its power under Article 15(4) and 16(4) of Indian

constitution as public employment and education." Further it was held

that the parliament alone is competent to pass such an act under the

article 341 of Indian constitution.

the Madigas are raising rapidly, but not to the extent of Malas. This

has led to a curious rivalry between the scheduled caste communities for

government benefits. The rivalry is legendary and traditional, going

back to tribal times

and manifested clearly in national and regional politics. Unfortunately

this tactic is used by the dominant upper castes to polarize both

groups and alienating them from political e mpowerment. Categorization

of SC’s by caste basis is primarily supported by selfish Upper caste

leaders who desperately try to preserve their power by promoting caste

based vote-bank politics. The Mala leaders have tried hard to convince

their madiga brothers about the ill effects of categorization but their

efforts were in vain as madigas under

have been aggressively working hard to pass the SC Categorization bill in Parliament

Malas oppose SC Categorization on 4 main grounds. They assert their stand saying that

Malas still live in segregated settlements in rural Andhra,but in

urban areas it is not so. Several pioneering members have taken to

education after tackling great discrimination and jeering : many

farsighted forward caste Hindus as well as Christian missionaries gave

them a boost—but the Malas put in the required effort. Overall the

community today clearly understands education is the key. Maaku sakti

ledu saar—we can't afford it (referring to children's education) is the

refrain heard over and over again especially in rural areas. However the

womenfolk are showing great determination, utilizing all avenues. The

unskilled farm laborers are gradually migrating to the towns and picking

up technical subjects as best as they can, and joining the service

workers and industrial workers. Some save up money to buy small farms

but these are a very small number. The

programs mandatory on the Government have also helped a very large

number to "rise" especially the educational programs. Some members have

benefited by joining the various bureaucracies.

.

This has its roots in the landholdings of the Reddis, where Malas are

said to be traditionally employed. Mala Christians, are the result of

conversions that had their origin in early 19th century, when

missionaries like Father Heyer evangelized parts of

.

These missionaries, later eatablished educational and cultural

institutions of great significance, across the erstwhile state of

Madras. Places like Guntur, Kurnool and Rajamundry, received a

voluminous boost in terms of education for the masses. This had led to a

mass upheaval in the cultural orientation of caste Hindus, as well as

converted Malas. Henceforth, a large chunk of the Mala population

embraced a biblical culture interspersed with traditional

characteristics from Hindu culture. Many theological colleges were

established across the state. These Christians from Andhra, found

gainful employment in mission schools and colleges, significantly

elevating their social position. They now form part of the upper middle

class sections of society. The Telugu land has seen umpteen men and

women of excellence, in various fields, from the Mala community.

Overall, at least in Andhra Pradesh and Maharashtra, the Mala-Mahar are

forging ahead very rapidly. They are very deeply attached to the works

of Dr.

. The Mala quarters in villages generally have a statue of Dr.

.

Karnataka and Maratha Pallans-Edgar Thurston

Kudumi or Kudumikkar.—

The Kudumis are mainly found in the sea-board taluks of Parūr, Shertally, and Ambalapuzha, in Travancore. The name is believed to be a corruption of the Sanskrit Kudumbi, meaning

[107]one connected with a family. By others it is derived from a Konkani word, meaning Sūdra. The popular name for the caste is Idiya (pounder), in reference to the occupation of pounding rice.

Kadiya, apparently derived from Ghatiyal, or a person possessed, is a term of reproach. The title Chetti is now assumed by members of the caste. But the well-known title is Mūppan, or elder, conferred on some respectable families by former Rājas of Cochin. The authority of the Trippanithoray Mūppan is supreme in all matters relating to the government of the caste. But his authority has passed, in Travancore, to the Turavūr Mūppan, who has supreme control over the twenty-two villages of Kudimis. The belief that the Mūppans differ from the rest of the Kudimis, so as to make them a distinct sept, does not appear to be based on fact. Nor is it true that the Mūppans represent the most ancient families of Konkana Sūdras, who emigrated to Kērala independently of the Konkanis. Chief among them is the Koratti Mūppan of Trippanithoray, who has, among other privileges, those of the drinking vessel and lighted lamp conferred on him by the Cochin rulers. Every Kudumi village has a local Mūppan. A few families enjoy the surname Kammatti, which is believed to be of agricultural origin.

The Kudumis speak a corrupt form of the Konkani dialect of

Marāthi. They are the descendants of these Konkana Sūdras, who emigrated from Goa on account of the persecutions of the Portuguese in the sixteenth century, and sought refuge along with their masters, the Konkana Brāhmans, on the coast of Travancore and Cochin. Most of them set out as the domestic servants of the latter, but a few were independent traders and agriculturists. Two varieties of rice grain, chethivirippu and malarnellu, brought by them from the Konkan, are

[108]still sown in Travancore. One of the earliest occupations, in which they engaged, was the manufacture of fireworks, and, as they were bold and sturdy, they were enlisted as soldiers by the chieftains of Malabar. Relics of the existence of military training-grounds are still to be found in many of their houses.

On a raised mud platform in the court-yard of the Kudumi’s house, the tulasi (Ocimum sanctum) or pīpal (Ficus religiosa) is invariably grown. Fish and flesh, except beef, are eaten, and intoxicating liquor is rather freely imbibed. The women wear coloured cloths, usually black, and widows are not obliged to be clad in white. A gold mukkutti is an indispensable nose ornament. Tattooing is largely resorted to by the women.

The occupation of the Kudumis is service in the houses of the Konkana Brāhmans. They also prepare beaten rice, act as boatmen, porters, and agricultural labourers, clean tanks and wells, and thatch houses. The Mūppans manufacture, and give displays of fireworks, which have a local reputation at the great Konkani temple of Turavūr in the Shertallay taluk.

They worship at the temples of the Konkana Brāhmans, as well as their own. But they are not pronounced Vaishnavites, like the Brāhmans, as the teachings of Madhvāchārya did not reach the lower ranks of Hinduism. On Sunday only one meal is taken. Maddu or Madan is their chief minor deity, and water-sheds are erected to propitiate him. Brahma is adored for nine days in the month of Kumbham (February-March) from the full-moon day. The pīpal tree is scrupulously worshipped, and a lighted lamp placed beside it every evening.

A woman, at the menstrual period, is considered impure for four days, and she stands at a distance of

[109]seven feet, closing her mouth and nostrils with the palm of the hand, as the breath of such a woman is believed to have a contaminating effect. Her shadow, too, should not fall on any one. The marriage of girls should take place before puberty. Violation of this rule would be punished by the excommunication of the family. During the marriage ceremony, the tulasi plant is worshipped, and the bride and bridegroom husk a small quantity of rice. The mother of the bridegroom prepares a new oven within the house, and places a new pot beside it. The contracting couple, assisted by five women, throw five handfuls of rice into the pot, which is cooked. They then put a quantity of paddy (unhusked rice) into a mortar, and after carefully husking it, make rice flour from it. A quantity of betel and rice is then received by the bride and bridegroom from four women. The tāli is tied round the bride’s neck by the bridegroom, and one of his companions then takes a thread, and fastens it to their legs. On the fifth day of the marriage rites, a piece of cloth, covering the breasts, is tied round the bride’s neck, and the nose is pierced for the insertion of the mukkutti.

Inheritance is generally from father to son (makkathāyam), but, in a few families, marumakkathāyam (inheritance through the female line) is observed. Widow remarriage is common, and the bridegroom is generally a widower. Only the oldest members of a family are cremated, the corpses of others being buried. The Kudumis own a common burial-ground in all places, where they reside in large numbers. Pollution lasts for sixteen days.

The Kudumis and the indigenous Sūdras of Travancore do not accept food from each other. They never wear the sacred thread, and may not enter the inner

[110]courtyard of a Brāhmanical temple. They remove pollution by means of water sprinkled over them by a Konkana Brāhman. Their favourite amusement is the koladi, in which ten or a dozen men execute a figure dance, armed with sticks, which they strike together keeping time to the music of songs relating to Krishna, and Bhagavati.

32

Telugu Pallars and Paraiyars - Malas or Chalavadi(Kuluvadi)

Māla.—

“The Mālas,” Mr. H. A. Stuart writes,

23 “are the Pariahs of the Telugu country. Dr. Oppert

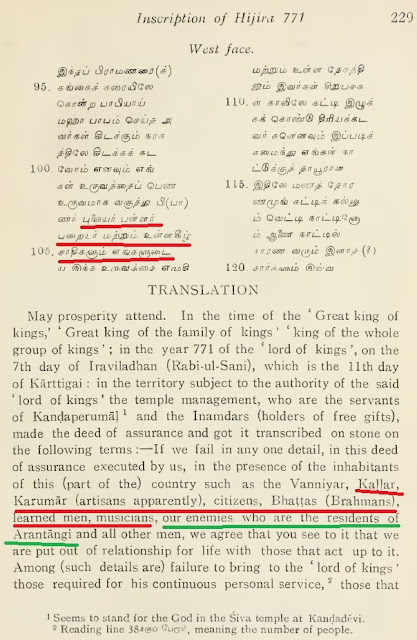

[330]derives the word from a Dravidian root meaning a mountain, which is represented by the Tamil malai, Telugu māla, etc., so that Māla is the equivalent of Paraiyan, and also of Mar or Mhar and the Māl of Western and Central Bengal. I cannot say whether there is sufficient ground for the assumption that the vowel of a Dravidian root can be lengthened in this way. I know of no other derivation of Māla. [In C. P. Brown’s Telugu Dictionary it is derived from maila, dirty.] The Mālas are almost equally inferior in position to the Mādigas. They eat beef and drink heavily, and are debarred entrance to the temples and the use of the ordinary village wells, and have to serve as their own barbers and washermen. They are the musicians of the community, and many of them (for example in the villages near Jammalamadugu in the Cuddapah district) weave the coarse white cotton fabrics usually worn by men.”

The Mālas will not take water from the same well as the Mādigas, whom they despise for eating carrion, though they eat beef themselves.

Both Mālas and Tamil Paraiyans belong to the right-hand section. In the Bellary district the Mālas are considered to be the servants of the Banajigas (traders), for whom they do certain services, and act as caste messengers (chalavāthi) on the occasion of marriages and funerals. At marriages, six Mālas selected from certain families, lead the procession, carrying flags, etc., and sit in the pial (verandah) of the marriage house. At funerals, a Māla carries the brass ladle bearing the insignia of the right-hand section, which is the emblem of the authority of the Dēsai or headman of the section.

The Mālas have their own dancing girls (Basavis), barbers, and musicians (Bainēdus), Dāsaris or priests,

[331]and beggars and bards called Māstigas and Pambalas (drum people), who earn their living by reciting stories of Ankamma, etc., during the funeral ceremonies of some Telugu castes, acting as musicians at marriages and festivals to the deities, begging, and telling fortunes. Other beggars are called Nityula (Nitiyadāsu, immortal). In some places, Tsākalas (washerman caste) will wash for the Mālas, but the clothes must be steeped in water, and left till the Tsākala comes for them. The Mālas will not eat food prepared or touched by Kamsalas, Mēdaras, Mādigas, Bēri Chettis, Bōyas, or Bhatrāzus. The condition of the Mālas has, in recent times, been ameliorated by their reception into mission schools.

In a case, which came before the High Court of Madras on appeal a few years ago, a Māla, who was a convert to Christianity, was sentenced to confinement in the stocks for using abusive language. The Judge, in summing up, stated that “the test seems to be not what is the offender’s creed, whether Muhammadan, Christian, or Hindu, but what is his caste. If he belongs to one of the lower castes, a change of creed would not of itself, in my judgment, make any difference, provided he continues to belong to the caste. If he continues to accept the rules of the caste in social and moral matters, acknowledges the authority of the headmen, takes part in caste meetings and ceremonies, and, in fact, generally continues to belong to the castes, then, in my judgment, he would be within the purview of the regulation. If, on the other hand, he adopts the moral standards of Christianity instead of those in his caste, if he accepts the authority of his pastors and teachers in place of that of the headman of the caste, if he no longer takes part in the distinctive meetings and

[332]ceremonies of the caste ... then he can no longer be said to belong to one of the lower castes of the people, and his punishment by confinement in the stocks is no longer legal.”

Between the Mālas and Mādigas there is no love lost, and the latter never allow the former, on the occasion of a festival, to go in palanquins or ride on horseback. Quite recently, in the Nellore district, a horse was being led at the head of a Mādiga marriage procession, and the Mālas followed, to see whether the bridegroom would mount it. To the disgust of the Mādigas, the young man refused to get on it, from fear lest he should fall off.

The Mālas will not touch leather shoes, and, if they are slippered with them, a fine is inflicted, and the money spent on drink.

Of the share which the Mālas take in a village festival in the Cuddapah district, an excellent account is given by Bishop Whitehead.

24 “The village officials and leading ryots,” he writes, “collect money for the festival, and buy, among other things, a barren sheep and two lambs. Peddamma and Chinnamma are represented by clay images of female form made for the occasion, and placed in a temporary shrine of cloth stretched over four poles. On the appointed evening, rice is brought, and poured out in front of the idol by the potter, and rice, ghī (clarified butter), and curds are poured on the top of it. The victims are then brought, and their heads cut off by a washerman. The heads are placed on the ground before the idol. The people then pour water on the heads, and say ‘speak’ (paluku). If the mouth opens, it is regarded as a sign that the goddess is

[333]propitious. Next, a large pot of boiled cholam (millet) is brought, and poured in a heap before the image, a little further away than the rice. Two buffaloes are then brought by the Mālas and Mādigas. One of the Mālas, called the Asādi, chants the praises of the goddess during the ceremony. The animals are killed by a Mādiga, by cutting their throats with a knife, one being offered to Peddamma, and the other to Chinnamma. Some of the cholam is then taken in baskets, and put under the throat of the buffaloes till it is soaked with blood, and then put aside. A Mādiga then cuts off the heads of the buffaloes with a sword, and places them before the idol. He also cuts off one of the forelegs of each, and puts it crosswise in the mouth. Some of the cholam is then put on the two heads, and two small earthen saucers are put upon it. The abdomens are then cut open, and some of the fat taken out, melted, and put in each saucer with a lighted wick. A layer of fat is spread over the eyes and mouths of the two heads, some of the refuse of the stomach is mixed with the cholam soaked in blood, and a quantity of margosa (

Melia Azadirachta) leaves put over the cholam. The Asādi then takes some of this mixture, and sprinkles it round the shrine, saying ‘Ko, bali,’

i.e., accept the sacrifice. Then the basket is given to another Māla, who asks permission from the village officials and ryots to sprinkle the cholam. He also asks that a lamb may be killed. The lamb is killed by a washerman, and the blood allowed to flow into the cholam in the basket. The bowels of the lamb are taken out, and tied round the wrist of the Māla who holds the basket, and puts it round his neck. He then goes and sprinkles the cholam mixed with blood, etc., in some cases round the village, and in others before each house, shouting ‘Ko, bali’ as he goes. The people go in

[334]procession with him, carrying swords and clubs to drive away evil spirits. During the procession, limes are cut in half, and thrown into the air to propitiate evil spirits. Other lambs are killed at intervals during the course of the procession. In the afternoon, the carcases of the two buffaloes offered the night before are taken away by the Mālas and Mādigas. One is cut open, and some of the flesh cooked near the shrine. Part of it, with some of the cholam offered before the images, is given to five Māla children, called Siddhulu,

i.e., holy or sinless, who, in some cases, are covered with a cloth during the meal. The rest is eaten by Mālas. The remainder of the carcases is divided among the Mālas and Mādigas, who take it to their own homes for a feast. The carcases of the lambs belong to the Mālas and washermen. The carcase of the barren sheep is the perquisite of the village officials, though the Kurnam, being a Brāhmin, gives his portion away.”

At a festival to the village goddess which is held at Dowlaishweram in the Godāvari district once every three years, a buffalo is sacrificed. “Votive offerings of pots of buttermilk are presented to the goddess, who is taken outside the village, and the pots are emptied there. The head of the buffalo and a pot of its blood are carried round the village by a Māla, and a pig is sacrificed in an unusual and cruel manner. It is buried up to its neck, and cattle are driven over it until it is trampled to death. This is supposed to ensure the health of men and cattle in the ensuing year.”

25

In connection with a village festival in the Godāvari district, Bishop Whitehead writes as follows.

26 “At Ellore, which is a town of considerable size and

[335]importance, I was told that in the annual festival of Mahālakshmi about ten thousand animals are killed in one day, rich people sending as many as twenty or thirty. The blood then flows down into the fields behind the place of sacrifice in a regular flood, and carts full of sand are brought to cover up what remains on the spot. The heads are piled up in a heap about fifteen feet high in front of the shrine, and a large earthen basin, about 1½ feet in diameter, is then filled with gingelly oil and put on the top of the heap, a thick cotton wick being placed in the basin and lighted. The animals are all worshipped with the usual namaskaram (folded hands raised to the forehead) before they are killed. This slaughter of victims goes on all day, and at midnight about twenty or twenty-five buffaloes are sacrificed, their heads being cut off by a Mādiga pūjāri (priest), and, together with the carcases, thrown upon the large heaps of rice, which have been presented to the goddess, till the rice is soaked with blood. The rice is collected in about ten or fifteen large baskets, and is carried on a large cart drawn by buffaloes or bullocks, with the Mādiga pūjāri seated on it. Mādigas sprinkle the rice along the streets and on the walls of the houses, as the cart goes along, shouting poli, poli (food). A large body of men of different castes, Pariahs and Sudras, go with the procession, but only the Mādigas and Mālas (the two sections of the Pariahs) shout poli, the rest following in silence. They have only two or three torches to show them the way, and no tom-toms or music. Apparently the idea is that, if they make a noise or display a blaze of lights, they will attract the evil spirits, who will swoop down on them and do them some injury, though in other villages it is supposed that a great deal of noise and flourishing of sticks will keep the evil spirits at bay.

[336]Before the procession starts, the heads of the buffaloes are put in front of the shrine, with the right forelegs in their mouths, and the fat from the entrails smeared about half an inch thick over the whole face, and a large earthen lamp on the top of each head. The Pambalas play tom-toms, and chant a long story about Gangamma till daybreak, and about 8

A.M.they put the buffalo heads into separate baskets with the lighted lamps upon them, and these are carried in procession through the town to the sound of tom-toms. All castes follow, shouting and singing. In former times, I was told, there was a good deal of fighting and disturbance during this procession, but now the police maintain order. When the procession arrives at the municipal limits, the heads are thrown over the boundary, and left there. The people then all bathe in the canal, and return home. On the last day of the festival, which, I may remark, lasts for about three months, a small cart is made of margosa wood, and a stake fixed at each of the four corners, and a pig and a fowl are tied to each stake, while a fruit, called dubakaya, is impaled on it instead of the animal. A yellow cloth, sprinkled with the blood of the buffaloes, is tied round the sides of the cart, and some margosa leaves are tied round the cloth. A Pambala sits on the cart, to which are fastened two large ropes, each about 200 yards long. Then men of all castes, without distinction, lay hold of the ropes, and drag the cart round the town to the sound of tom-toms and music. Finally it is brought outside the municipal limits and left there, the Pariahs taking away the animals and fruits.”

The following detailed account of the Peddamma or Sunkulamma jātra (festival) in the Kurnool district, is given in the Manual. “This is a ceremony strictly

[337]local, in which the entire community of a village takes part, and which all outsiders are excluded from participating in. It is performed whenever a series of crops successively fail or cattle die in large numbers of murrain, and is peculiarly adapted, by the horrible nature of the attendant rites and the midnight hour chosen for the exhibition of its most ghastly scenes, to impress the minds of an ignorant people with a belief in its efficacy. When the celebration of the jātra is resolved on, a dark Tuesday night is selected for it, and subscriptions are collected and deposited with the Reddi (headman) or some respectable man in the village. Messengers are sent off to give intimation of the day fixed for the jātra to the Bynēnivādu, Bhutabaligādu, and Poturāju, three of the principal actors in the ceremony. At the same time a buffalo is purchased, and, after having its horns painted with saffron (turmeric) and adorned with margosa leaves, is taken round the village in procession with tom-toms beating, and specially devoted to the sacrifice of the goddess Peddamma or Sunkulamma on the morning of the Tuesday on which the ceremony is to take place. The village potter and carpenter are sent for, and ordered to have ready by that evening two images of the goddess, one of clay and the other of juvi wood, and a new cloth and a quantity of rice and dholl (peas:

Cajanus indicus) are given to each of them. When the images are made, they are dressed with the new cloths, and the rice and dholl are cooked and offered as naivēdyam to the images. In some villages only one image, of clay, is made. Meanwhile the villagers are busy erecting a pandal (booth) in front of the village chāvidi (caste meeting-house), underneath which a small temple is erected of cholam straw. The Bynēnivādu takes a handful of earth, and places it inside this little temple, and

[338]the village washerman builds a small pyal (dais) with it, and decorates it with rati (streaks of different coloured powders). New pots are distributed by the potter to the villagers, who, according to their respective capabilities, have a large or small quantity of rice cooked in them, to be offered as kumbham at the proper time. After dark, when these preparations are over, the entire village community, including the twelve classes of village servants, turn out in a body, and, preceded by the Bynēnivādu and Asādivandlu, proceed in procession with music playing to the house of the village potter. There the image of the goddess is duly worshipped, and a quantity of raw rice is tied round it with a cloth. A ram is sacrificed on the spot, and several limes are cut and thrown away. Borne on the shoulders of the potter, the image is then taken through the streets of the village, Bynēnivādu and Asādivandlu dancing and capering all the way, and the streets being drenched with the blood of several rams sacrificed at every turning of the road, and strewed with hundreds of limes cut and thrown away. The image is then finally deposited in the temple of straw already referred to, and another sheep is sacrificed as soon as this is done. The wooden image, made by the carpenter, is also brought in with the same formalities, and placed by the side of the image of clay. A pot of toddy is similarly brought in from the house of the Īdigavādu (toddy-drawer), and set before the images. Now the dēvarapōtu, or buffalo specially devoted to the sacrifice of the goddess, is led in from the Reddi’s house in procession, together with a sheep and a large pot of cooked rice. The rice in the pot is emptied in front of the images and formed into a heap, which is called the kumbham, and to it are added the contents of many new pots, which the villagers have ready filled with cooked

[339]rice. The sheep is then sacrificed, and its blood shed on the heap. Next comes the turn of the dēvarapōtu, the blood of which also, after it has been killed, is poured over the rice heap. This is followed by the slaughter of many more buffaloes and sheep by individuals of the community, who might have taken vows to offer sacrifices to the goddess on this occasion. While the carnage is going on, a strict watch is kept on all sides, to see that no outsider enters the village, or steals away any portion of the blood of the slaughtered animals, as it is believed that all the benefit which the villagers hope to reap from the performance of the jātra will be lost to them if an outsider should succeed in taking away a little of the blood to his village. The sacrifice being over, the head and leg of one of the slaughtered buffaloes are severed from its body, and placed before the goddess with the leg inserted into the mouth of the head. Over this head is placed a lighted lamp, which is fed with oil and buffalo’s fat. Now starts a fresh procession to go round the village streets. A portion of the kumbham or blood-stained rice heaped up before the image is gathered into two or three baskets, and carried with the procession by washermen or Mādigas. The Bhutabaligādu now steps forward in a state of perfect nudity, with his body clean shaven from top to toe, and smeared all over with gore, and, taking up handfuls of rice (called poli) from the baskets, scatters them broadcast over the streets. As the procession passes on, bhutams or supernatural beings are supposed to become visible at short distances to the carriers of the rice baskets, who pretend to fall into trances, and, complaining of thirst, call for more blood to quench it. Every time this happens, a fresh sheep is sacrificed, and sometimes limes are cut and thrown in their way. The main streets being thus

[340]sprinkled over with poli or blood-stained rice, the lanes or gulleys are attended to by the washermen of the village, who give them their share of the poli. By this time generally the day dawns, and the goddess is brought back to her straw temple, where she again receives offerings of cooked rice from all classes of people in the village, Brāhmins downwards. All the while, the Asādivandlu keep singing and dancing before the goddess. As the day advances, a pig is half buried at the entrance of the village, and all the village cattle are driven over it. The cattle are sprinkled over with poli as they pass over the pig. The Poturāju then bathes and purifies himself, and goes to the temple of Lingamayya or Siva with tom-toms and music, and sacrifices a sheep there. The jātra ends with another grand procession, in which the images of the goddess, borne on the heads of the village potter and carpenter, are carried to the outskirts of the village, where they are left. As the villagers return home, they pull to pieces the straw temple constructed in front of the chāvidi, and each man takes home a straw, which he preserves as a sacred relic. From the day the ceremony is commenced in the village till its close, no man would go to a neighbouring village, or, if he does on pressing business, he would return to sleep in his own village. It is believed that the performance of this jātra will ensure prosperity and health to the villagers and their cattle.

“The origin of this Sunkulamma jātra is based on the following legend, which is sung by the Bynēni and Asādivandlu when they dance before the images. Sunkulamma was the only daughter of a learned Brāhmin pandit, who occasionally took pupils, and instructed them in the Hindu shastras gratuitously. One day, a handsome youth of sixteen years came to the pandit,

[341]and, announcing himself as the son of a Brāhmin of Benares come in quest of knowledge, requested that he might be enlisted as a pupil of the pandit. The pandit, not doubting the statement of the youth that he was a Brāhmin, took him as a pupil, and lodged him in his own house. The lad soon displayed marks of intelligence, and, by close application to his studies, made such rapid progress that he became the principal favourite of his master, who was so much pleased with him that, at the close of his studies, he married him to his daughter Sunkulamma. The unknown youth stayed with his father-in-law till he became father of some children, when he requested permission to return to his native place with his wife and children, which was granted, and he accordingly started on his homeward journey. On the way he met a party of Māla people, who, recognising him at once as a man of their own caste and a relation, accosted him, and began to talk to him familiarly. Finding it impossible to conceal the truth from his wife any longer, the husband of Sunkulamma confessed to her that he was a Mala by caste, and, being moved by a strong desire to learn the Hindu shastras, which he was forbidden to read, he disguised himself as a Brāhmin youth, and introduced himself to her father and compassed his object; and, as what had been done in respect to her could not be undone, the best thing she could do was to stay with him with her children. Sunkulamma, however, was not to be so persuaded. Indignant at the treachery practiced on her and her parent, she spurned both her husband and children, and returning to her village, sent for her parent, whose house she would not pollute by going in, and asked him what he would do with a pot denied by the touch of a dog. The father replied that he would commit it to the flames

[342]to purify it. Taking the hint, she caused a funeral pile to be erected, and committed suicide by throwing herself into the flames. But, before doing so, she cursed the treacherous Māla who bad polluted her that he might become a buffalo, and his children turn into sheep, and vowed she would revive as an evil spirit, and have him and his children sacrificed to her, and get his leg put into his mouth, and a light placed on his head fed with his own fat.”

The following additional information in connection with the jātra may be recorded. In some places, on a Tuesday fifteen days before the festival, some Mālas go in procession through the main streets of the village without any noise or music. This is called mūgi chātu (dumb announcement). On the following Tuesday, the Mālas go through the streets, beating tom-toms, and proclaiming the forthcoming ceremony. This is called chātu (announcement). In some villages, metal idols are used. The image is usually in the custody of a Tsākala (washerman). On the jātra day, he brings it fully decorated, and sets it up on the Gangamma mitta (Gangamma’s dais). In some places, this is a permanent structure, and in others put up for the jātra at a fixed spot. Āsādis, Pambalas, and Bainēdus, and Mādiga Kommula vāndlu (horn-blowers) dance and sing until the goddess is lifted up from the dais, when a number of burning torches are collected together, and some resinous material is thrown into the flames. At the same time, a cock is killed, and waved in front of the goddess by the Tsākala. A mark is made with the blood on the forehead of the idol, which is removed to a hut constructed by Mālas with twigs of margosa (

Melia Azadirachta),

Eugenia Jambolana and

Vitex Negundo. In some villages, when the goddess is brought in

[343]procession to the outskirts of the village, a stick is thrown down in front of her. The Āsādis then sing songs, firstly of a most obscene character, and afterwards in praise of the goddess.

The following account of “the only Māla ascetic in Bharatavarsha” (India) is given by Mr. M. N. Vincent.

27 The ascetic was living on a hill in Bezwāda, at the foot of which lay the hamlets of the Mālas. The man, Govindoo by name, “was a groom in the employ of a Muhammadan Inspector of Police, and he was commissioned on one occasion to take a horse to a certain town. He was executing his commission, when, on the way, and not far from his destination, the animal shied and fell into the Krishna river, and was swept along the current, and poor Govindoo could not help it. But, knowing the choleric temper of his employer, and in order to avoid a scolding, he roamed at large, and eventually fell in with a company of Sādhus, one of whose disciples he became, and practiced austerities, though not for the full term, and settled eventually on the hill where we saw him occupying the old cave dwelling of a former Sādhu. It appears that there was something earthly in the man, Sādhu though he was, as was evidenced from his relations with a woman votary or disciple, and it was probably because of this phase of his character that some people regarded him as a cheat and a rogue. But this unfavourable impression was soon removed, and, since the time he slept on a bed of sharp thorns, as it were in vindication of his character, faulty though it had been, he has been honoured. A good trait in the man should be mentioned, namely, that he wrote to his parents to give his wife in

[344]marriage to some one else, as he had renounced his worldly ties.”

At Vānavōlu, in the Hindupūr tāluk of the Anantapūr district, there is a temple to Rangaswāmi, at which the pūjari (priest) is a Māla. People of the upper castes frequent it, but do their own pūja, the Māla standing aside for the time.

28

It is noted, in the Madras Census Report, 1891, that the chief object of worship by the Balijas is Gauri, their caste deity. “It is said that the Mālas are the hereditary custodians of the idol of Gauri and her jewels, which the Balijas get from them whenever they want to worship her. The following story is told to account for this. The Kāpus and the Balijas, molested by the Muhammadan invaders on the north of the river Pennār, migrated to the south when the Pennār was in full flood. Being unable to cross the river, they invoked their deity to make a passage for them, for which it demanded the sacrifice of a first-born child. While they stood at a loss what to do, the Mālas, who followed them, boldly offered one of their children to the goddess. Immediately the river divided before them, and the Kāpus and the Balijas crossed it, and were saved from the tyranny of the Muhammadans. Ever since that time, the Mālas have been respected by the Kāpus and Balijas, and the latter even deposited the images of Gauri, the bull and Ganēsa, which they worshipped in the house of a Māla. I am credibly informed that the practice of leaving these images in the custody of Mālas is even now observed in some parts of Cuddapah district and elsewhere.”

An expert Māla medicine-man has been known to prescribe for a Brāhman tahsildar (revenue officer),

[345]though the consultation was conducted at a most respectful distance on the part of the honoured physician.

Māla weavers are known as Netpanivandlu (Nethapani, weaving work). According to the Census Report, 1891, the sub-divisions of the Mālas, which are numerically strongest, are Arava, Kanta, Murikinādu, Pākanāti, and Reddi Bhūmi. To these may be added Sarindla, Sāvu, Sāindla, and Dāindla. Concerning some of these divisions, the following legend is current. A Māla married eighteen wives, one from each kulam or tribal division. The god Poleramma, objecting to the sacrifice of sheep and goats, wanted him to offer up a woman and child in substitution for the animals, and the Māla broke the news to his wives, one of whom eloped with a Reddi, and gave origin to the Reddi Bhūmis (bhūmi, earth). Another ran away, and gave rise to the Pākanātis (eastern country). A third hid herself, and escaped by hiding. Hence her descendants are called Dāindla vāndlu, concerning whom there is a proverb “Dagipoyina vāndlu Dāindla vāndlu” or “Those who escaped by hiding are Dāindlas.” One of the wives, who fled to the forest, found her way out by clearing the jungle, and her descendants are called Sarindla (straight). The wife who consented to be sacrificed with her child was restored to life by Poleramma, and gave rise to the Sāvu (death) or Sāindla (belonging to a death house) section. The Dāindlas are said to be Tamil Paraiyans, who settled down in the Telugu country, and adopted the manners and customs of the Mālas. Some call themselves Arava (Tamil) Mālas. They are employed as servants in European houses, horse-keepers, etc.

In connection with the origin of the Mālas, the Rev. S. Nicholson writes as follows. “Originally the Mālas belonged to the kudi paita section of the community,

[346]i.e., their women wore the cloth over the right shoulder, but now there are both right and left paita sections, and this must be taken as the principal division. The right-hand (right paita) section is again divided into (

a) Reddi Bhūmalavaru, (

b) Pōkunātivaru. The left-hand (left paita) section are Murikinātivaru. The following legend professes to account for the existence of the three divisions. When Vīrabahuvu went to the rescue of Harischandra, he promised Kāli that, if she granted him success, he would sacrifice to her his wives, of whom he had three. Accordingly, after his conquest of Vishvamithrudu, he returned, and called his wives that he might take them to the temple in order to fulfil his vow. The wives got some inkling of what was in store for them, and one of them took refuge in the house of a Reddi Bhūmala, another ran away to the eastern country (Pōkunāti), while the third, though recently confined, and still in her dirty (muriki) cloth, determined to abide by the wish of her lord. She was, therefore, sacrificed to Kāli, but the goddess, seeing her devotion, restored her to life, and promised to remain for ever her helper. The reason given for the change in the method of wearing the cloth is that, after the incident described above took place, the women of the Murikināti section, in order to express their disapproval of the two unfaithful wives, began to wear their cloths on the opposite, viz., the left, shoulder. In marriages, however, whatever the paita of the bride, she must wear the cloth over the right shoulder.

“The Reddi Bhūmalu and Pōkunātivāru say that the reason they wear the cloth over the right shoulder is that they are descendants of the gods. According to a legend, the goddess Parvati, whilst on a journey with her lord Paramēshvarudu, discarded one of her unclean

[347](maila) cloths, from which was born a little boy. This boy was engaged as a cattle-herd in the house of Paramēshvarudu. Parvati received strict injunctions from her lord that she should on no account allow the little Māla to taste cream. One day, however, the boy discovered some cream which had been scraped from the inside of the pot sticking to a wall. He tasted it, and found it good. Indeed, so good was it that he came to the conclusion that the udder from which it came must be even better still. So one day, in order to test his theory, he killed the cow. Then came Paramēshvarudu in great anger, and asked him what he had done, and, to his credit be it said, the boy told the truth. Then Paramēshvarudu cursed the lad and all his descendants, and said that from henceforth cattle should be the meat of the Mālas—the unclean.”

The Mālas have, in their various sub-divisions, many exogamous septs, of which the following are examples:—

(a) Reddi Bhūmi.

- Avuka, marsh.

- Bandi, cart.

- Bommala, dolls.

- Bejjam, holes.

- Dakku, fear.

- Dhidla, platform or back-door.

- Dhōma, gnat or mosquito.

- Gēra, street.

- Kaila, measuring grain in threshing-floor.

|

- Kātika, collyrium.

- Naththalu, snails.

- Paida, money or gold.

- Pilli, cat.

- Rāyi, stone.

- Samūdrala, ocean.

- Sīlam, good conduct.

- Thanda, bottom of a ship.

|

(b) Pōkunāti.

- Allam, ginger.

- Dara, stream of water.

- Gādi, cart.

- Gōne, sack.

- Gurram, horse.

- Maggam, loom.

|

- Mailāri, washerman.

- Parvatha, mountain.

- Pindi, flour-powder.

- Pasala, cow.

- Thummala, sneezing.

|

(c) Sarindla.

- Boori, a kind of cake.

- Ballem, spear.

- Bomidi, a fish.

- Challa, butter milk.

- Chinthala, tamarind.

- Duddu, money.

- Gāli, wind.

- Karna, ear.

- Kāki, crow.

|

- Mudi, knot.

- Maddili, drum.

- Malle, jasmine.

- Putta, ant-hill.

- Pamula, snake.

- Pidigi, handful.

- Semmati, hammer.

- Uyyala, see-saw.

|

(d) Dāindla.

- Dāsari, priest.

- Doddi, court or backyard.

- Gonji, Glycosmis pentaphylla.

- Kommala, horn.

|

- Marri, Ficus bengalensis.

- Pala, milk.

- Powāku, tobacco.

- Thumma, Acacia arabica.

|

Concerning the home of the Mālas, Mr. Nicholson writes that “the houses (with mud or stone walls, roofed with thatch or palmyra palm leaves) are almost invariably placed quite apart from the village proper. Gradually, as the caste system and fear of defilement become less, so gradually the distance of their houses from the village is becoming less. In the Ceded Districts, where from early times every village was surrounded by a wall and moat, the aloofness of the houses is very apparent. Gradually, however, the walls are decaying, and the moats are being filled, and the physical separation of the outcaste classes is becoming less apparent.”

Mr. Nicholson writes further that “according to their own traditions, as told still by the old people and the religious mendicants, in former times the Mālas were a tribe of free lances, who, ‘like the tiger, slept during the day, and worked at night.’ They were evidently the paid mercenaries of the Poligars (feudal chiefs), and carried out raids and committed robberies for the lord

[349]under whose protection they were. That this tradition has some foundation may be gathered from the fact that many of the house-names of the Mālas refer to weapons of war,

e.g., spear, drum, etc. If reports are true, the old instinct is not quite dead, and even to-day a cattle-stealing expedition comes not amiss to some. The Mālas belong to the subjugated race, and have been made into the servants of the community. Very probably, in former days, their services had to be rendered for nothing, but later certain inām (rent-free) lands were granted, the produce of which was counted as remuneration for service rendered. Originally, these lands were held quite free of taxation, but, since the advent of the British Rāj, the village servants have all been paid a certain sum per month, and, whilst still allowed the enjoyment of their inām lands, they have now been assessed, and half the actual tax has to be paid to Government. The services rendered by the Mālas are temple service, jātra or festival service, and village service. The village service consists of sweeping, scavenging, carrying burdens, and grave-digging, the last having been their perquisite for long ages. According to them, the right was granted to them by King Harischandra himself. The burial-grounds are supposed to belong to the Mālas, and the site of a grave must be paid for, the price varying according to the position and wealth of the deceased, but I hear that, in our part of the country, the price does not often exceed two pence. Though the Brāhmans do not bury, yet they must pay a fee of one rupee for the privilege of burning, besides the fee for carrying the body to the ghāt. There is very little respect shown by the Mālas at the burning-ghāt, and the fuel is thrown on with jokes and laughter. The Mālas dig graves for all castes which bury, except

[350]Muhammadans, Oddēs, and Mādigas. Not only on the day of burial, but afterwards on the two occasions of the ceremonies for the dead, the grave-diggers must be given food and drink. The Mālas are also used as death messengers to relatives by all the Sūdra castes. When on this work, the messenger must not on any account go to the houses of his relatives though they live in the village to which he has been sent.

“The chief occupations of the Mālas are weaving, and working as farm labourers for Sūdras; a few cultivate their own land. Though formerly their inām lands were extensive, they have been, in the majority of cases, mortgaged away. The Mālas of the western part of the Telugu country are of a superior type to those of the east, and they have largely retained their lands, and, in some cases, are well-to-do cultivators. In the east, weaving is the staple industry, and it is still carried on with the most primitive instruments. In one corner of a room stands the loom, with a hole in the mud floor to receive the treadles, and a little window in the wall, level with the floor, lights the web. The loom itself is slung from the rafters, and the whole can be folded up and put away in a corner. As a rule, weaving lasts for eight months of the year, the remainder of the year being occupied in reaping and stacking crops, etc. Each weaver has his own customers, and very often one family of Mālas will have weaved for one family of Sūdras for generations. Before starting to weave, the weaver worships his loom, and rubs his shuttle on his nose, which is supposed to make it smooth. Those who cannot weave subsist by day labour. As a rule, they stick to one master, and are engaged in cultivation all the year round. Many, having borrowed money from

[351]some Sūdra, are bound to work for him for a mere pittance, and that in grain, not cash.”

In a note on a visit to Jammalamadugu in the Cuddapah district, Bishop Whitehead writes as follows.

29 “Lately Mr. Macnair has made an effort to improve the methods of weaving, and he showed us some looms that he had set up in his compound to teach the people the use of a cheap kind of fly-shuttle to take the place of the hand-shuttle which is universally used by the people. The difficulties he has met with are characteristic of many attempts to improve on the customs and methods of India. At present the thread used for the hand-shuttle is spun by the Māla women from the ordinary cotton produced in the district. The Māla weavers do not provide their own cotton for the clothes they weave, but the Kāpus give them the cotton from their own fields, pay the women a few annas for spinning it, and then pay the men a regular wage for weaving it into cloth. But the cotton spun in the district is not strong enough for the fly-shuttle, which can only be profitably worked with mill-made thread. The result is that, if the fly-shuttle were generally adopted, it would leave no market for the native cotton, throw the women out of work, upset the whole system on which the weavers work, and, in fact, produce widespread misery and confusion!”

The following detailed account of the ceremonies in connection with marriage, many of which are copied from the higher Telugu castes, is given by Mr. Nicholson. “Chinna Tāmbūlam (little betel) is the name given to the earliest arrangements for a future wedding. The parents of the boy about to be married enquire of a

[352]Brāhman to which quarter they should go in search of a bride. He, after receiving his pay, consults the boy’s horoscope, and then tells them that in a certain quarter there is loss, in another quarter there is death, but that in another quarter there is gain or good. If in the quarter which the Brāhman has intimated as good there are relations, so much the better; the bride will be sought amongst them. If not, the parents of the youth, along with an elder of the caste, set out in search of a bride amongst new people. On reaching the village, they do not make their object known, but let it appear that they are on ordinary business. Having discovered a house in which there is a marriageable girl, after the ordinary salutations, they, in a round-about way, make enquiries as to whether the warasa or marriage line is right or not. If it is all right, and if at that particular time the girl’s people are in a prosperous condition, the object of the search is made known. If, on the other hand, the girl’s people are in distress or grief, the young man’s party go away without making their intention known. Everything being satisfactory, betel nut and leaves are offered, and, if the girl’s people are willing to contract, they accept it; if not, and they refuse, the search has to be resumed. We will take it for granted that the betel is accepted. The girl’s parents then say ‘If it is God’s will, so let it be; return in eight or nine days, and we will give you our answer.’ If, within that time, there should be death or trouble of any sort in either of the houses, all arrangements are abandoned. If, when going to pay the second visit, on the journey any of the party should drop on the way either staff or bundle of food, it is regarded as a bad omen, and further progress is stopped for that day. After reaching the house of the prospective bride on the second occasion,

[353]the party wait outside. Should the parents of the girl bring out water for them to drink and to wash their faces, it is a sign that matters may be proceeded with. Betel is again distributed. In the evening, the four parents and the elders talk matters over, and, if all is so far satisfactory, they promise to come to the house of the future bridegroom on a certain date. The boy’s parents, after again distributing betel, this time to every house of the caste, take their departure. When the party of the bride arrive at the boy’s village, they are treated to toddy and a good feed, after which they give their final promise. Then, having made arrangements for the Pedda Tāmbūlam (big betel), they take their departure. This ends the first part of the

negotiations. Chinna Tāmbūlam is not binding. The second part of the negociations, which is called Pedda Tāmbūlam, takes place at the home of the future bride. Before departing for the ceremony, the party of the bridegroom, which must be an odd number but not seven, and some of the elders of the village, take part in a feast. The members of the party put on their religious marks, daub their necks and faces with sandal paste and akshinthulu (coloured rice), and are sent off with the good wishes of the villagers. After the party has gone some few miles, it is customary for them to fortify themselves with toddy, and to distribute betel. The father of the groom takes with him as a present for the bride a bodice, fried dal (pea:

Cajanus indicus), cocoanut, rice, jaggery, turmeric, dates, ghī, etc. On arrival at the house, the party wait outside, until water is brought for their faces and feet. After the stains of travel have been washed off, the presents are given, and the whole assembly proceeds to the toddy shop. On their return, the Chalavādhi (caste servant) tells

[354]them to which households betel must be presented, after which the real business commences. The party of the bridegroom, the people of the bride, the elders of the caste, and one person from each house in the caste quarter, are present. A blanket is spread on the floor, and grains of rice are arranged on it according to a certain pattern. This is the bridal throne. After bathing, the girl is arrayed in an old cloth, and seated on a weaver’s beam placed upon the blanket, with her face towards the east. Before seating herself, however, she must worship towards the setting sun. In her open hands betel is placed, along with the dowry (usually about sixteen rupees) brought by her future father-in-law. As the bride sits thus upon the throne, the respective parents question one another, the bride’s parents as to the groom, what work he does, what jewels he will give, etc. Whatever other jewels are given or not, the groom is supposed to give a necklace of silver and beads, and a gold nose jewel. As these things are being talked over, some one winds 101 strands of thread, without twisting it, into a circle about the size of a necklace, and then ties on it a peculiar knot. After smearing with turmeric, it is given into the hands of the girl’s maternal uncle, who, while holding his hands full of betel, asks first the girl’s parents, and then the whole community if there is any objection to the match. If all agree, he must then worship the bridal throne, and, without letting any of the betel in his hands fall, place the necklace round the bride’s neck. Should any of the betel fall, it is looked upon as a very bad omen, and the man is fined. After this part of the performance is over, and after teasing the bride, the uncle raises her to her feet, and, taking from her hands the dowry, etc., sends her off. After distributing betel to every one in the

[355]village, even unborn babies being counted, the ceremony ends, and, after the usual feast has been partaken of, the people all depart to their various homes.

“The wedding, contrary to the previous ceremonies, takes place at the home of the bridegroom. A Brāhman is asked to tell a day on which the omens are favourable, for which telling he receives a small fee. A few days before the date foretold, the house is cleaned, the floor cow-dunged, and the walls are whitewashed. In order that the evil eye may be warded off, two marks are made, one on each side of the door, with oil and charcoal mixed. Then the clothes of the bride and bridegroom are made ready. These, as a rule, are yellow and white, but on no account must there be any indigo in them, as that would be a sign of death. The grain and betel required for the feast, a toe-ring for the bridegroom, and a tāli (marriage badge) for the bride, are then purchased. The toe-ring is worn on the second toe of the right foot, and the tāli, which is usually about the size of a sixpence, is worn round the woman’s neck. The goldsmith is paid for these not only in coin, but also in grain and betel, after receiving which he blesses the jewels he has made, and presents them to the people. Meanwhile, messengers have been sent, with the usual presents, to the bride’s people and friends, to inform them that the auspicious day has been fixed, and bidding them to the ceremony. In all probability, before the preparations mentioned above are complete, all the money the bridegroom’s people have saved will be expended. But there is seldom any difficulty in obtaining a loan. It is considered an act of great merit to advance money for a wedding, and people of other and richer castes are quite ready to lend the amount required. In former days, it was customary to give these loans free of interest,

[356]but it is not so now. The next item is the preparation of the pandal or bower. This is generally erected a day or two before the actual marriage in front of the house. It consists of four posts, one at each corner, and the roof is thatched with the straw of large millet. All round are hung garlands of mango leaves, and cocoanut leaves are tied to the four posts. On the left side of the house door is planted a branch of a tree (

Nerium odorum), to which is attached the kankanam made in the following way. A woollen thread and a cotton thread are twisted together, and to them are tied a copper finger-ring, a piece of turmeric root, and a betel leaf. The tree mentioned is watered every day, until the whole of the marriage ceremonies are completed. As a rule, the whole of the work in connection with the erection of the pandal is carried out by the elders, who receive in payment food and toddy. At this time, also, the fire-places for the cooking of the extra amount of food are prepared. These are simply trenches dug in the mud floor of the house, usually three in number. Before they are dug, a cocoanut is broken, and offered over the spot. A journey is now made to the potter’s for the pots required in the cooking of the marriage feast. This in itself is quite a ceremony. A canopy is formed of an ordinary wearing cloth supported at its four corners by four men, whilst a boy with a long stick pushes it into a tent shape in the middle. Beneath the canopy is one of the women of the bridegroom’s family, who carries on a tray two sacred lamps, an eight-anna piece, some saffron (turmeric), akshinthulu, betel, frankincense, cocoanut, etc. On arriving at the potter’s house, the required pots are placed in a row outside, and a cocoanut, which has been held in the smoke of the incense, is broken into two equal parts, the

[357]two halves being placed on the ground about a yard apart. To these all the people do pūja (worship), and then take up the pots, and go home. The eight-anna piece is given to the potter, and the betel to the Chalavādhi. On the way to the potter’s, and on the return thence, the procession is accompanied with music, and the women sing songs. Meanwhile, the groom, and those who have remained at home, have been worshipping the goddess Sunkalamma. The method of making this goddess, and its worship, are as follows. Rice and green gram are cooked together, and with this cooked food a cone is made minus the point. A little hollow is made on the top, and this is filled with ghī (clarified butter), onions, and dal. Four wicks are put into it, so forming a lamp. A nose jewel is stuck somewhere on the outside of the lump, two garlands are placed round it, and the whole is decorated with religious marks. This goddess is always placed in the north-east corner of the house, called the god’s corner, which has been previously cleaned, and an image of Hanumān, or some other deity, is drawn with rice-powder on the floor. Upon this drawing the image of Sunkalamma is placed. Before her are put several little balls of rice, with which ghī has been mixed. The worship consists in making offerings of frankincense and camphor, and a cocoanut, which is broken in half, the halves being put in front of the goddess. A ram or a he-goat is now brought, nīm (

Melia Azadirachta) leaves are tied round the horns, religious marks are made on the forehead, water is placed in its mouth, and it is then sacrificed. After the sacrifice has been made, those assembled prostrate themselves before the image for some time in silence, after which they go outside for a minute or two, and then, returning, divide the goddess,

[358]and eat it. The groom now has his head shaved, and the priest cuts his finger and toe nails, eyelashes, etc. The cuttings are placed, along with a quarter of a rupee which he has kept in his mouth during the process, in an old winnowing tray, with a little lamp made of rice, betel and grain. The priest, facing west and with the bridegroom in front of him, makes three passes with the tray from the head to the foot. This is supposed to take away the evil eye. The priest then takes the tray away, all the people getting out of the way lest the blight should come on them. He throws away what is useless, but keeps the rest, especially the quarter of a rupee. After this little ceremony, the future husband takes a bath, but still keeps on his old clothes. He is given a knife, with which to keep away devils, and is garlanded with the garlands which were round the goddess. His toe-ring is put on, and the next ceremony, the propitiation of the dead, is proceeded with. The sacrificed animal is dismembered, and the bones, flesh, and intestines are put into separate pots, and cooked. Rice also is prepared, and placed in a heap, to which the usual offerings are made. Then rice, and some of the flesh from each pot, is placed upon two leaf plates. These are left before the heap of rice, with two lamps burning. The people all salute the rice, and proceed to eat it. The rice on the two plates is reserved for members of the family. By this time, the bride has most likely arrived in the village, but, up to this stage, will have remained in a separate house. She does not come to the feast mentioned above, but has a portion of food sent to her by the bridegroom’s people. After the feast, bride and bridegroom are each anointed in their separate houses with nalugu (uncooked rice and turmeric). When the anointing of the bride takes place,

[359]the groom sends to her a cloth, a bodice, cocoanut, pepper and garlic. The bride leaves her parents’ house, dressed in old clothes. Her people provide only a pair of sandals, and two small toe-rings. She also carries a fair quantity of rice in the front fold of her cloth. Again a procession is formed as before for the cooking-pots, and another visit is paid to the potter’s house, but, on this occasion, in place of eight annas grain is taken. The potter presents them with two wide-mouthed pots, and four small-mouthed pots, two of which are decorated in four colours. As before, these are placed in a row outside, and again the party, after worshipping them, takes them to the bridegroom’s house. These pots are supposed to represent Lakshmi, the goddess of wealth, and, as they are being carried to the house, no pregnant woman or mother with small children should meet them, or they will have trouble. On arriving at the house, and before entering, a cock is sacrificed, and a cocoanut offered. [In some places, a goat is killed in front of the room in which the marriage pots are kept, and marks are made with the palms of the hands covered with the blood on the side-walls of the entrance.] Water is sprinkled on the door step, and the pots are taken inside. During the whole of the above performance, the pots are held in the hands, and must not be put down. After entering the house, grain is spread on the floor in the north-east corner, and upon this are placed the pots, one upon the other, in two or four rows. The topmost pot is covered with a lid, and on the lid is placed a lighted lamp. From the beams exactly above the lamps are suspended, to which are fastened small bundles containing dates, cocoanut, jaggery, sugar, and saffron. Round each pot is tied a kankanam (wrist-thread). These pots are worshipped every day as long

[360]as the wedding ceremonies last, which is usually three days. Not only so, but the lamps are kept continually burning, and there is betel arranged in a brass pot in the form of a lotus ever before them. Beneath the pandal is now arranged a throne exactly similar to the one which was used on the occasion of the Pedda Tāmbūlam. Until now the bride has kept to her separate house, but she now dresses in her new clothes. Putting on the sandals she brought from her own home, she proceeds to the house of the bridegroom. There she waits in the pandal for her future husband, who comes out dressed in his wedding garments, wearing his sandals, and carrying a blanket, gōchi,

30 shoulder-cloth, and knife. Both bride and bridegroom now have fastened on to their foreheads a kind of philactery or nuptial crown called bhāsingalu. They are also garlanded with flowers, in addition to which the bridegroom has tied on to his wrists the kankanam. In order that the two most intimately concerned persons may not see one another (and up to this point they have not done so), a screen is erected, the bride standing on one side, and the bridegroom on the other. As a rule, they each of them keep their heads bent during the whole of the proceedings, and look as miserable as possible. Indeed, it would be a breach of etiquette for either of them to appear as though they were enjoying the ceremony. Except for the screen, the two are now face to face, the groom looking towards the east, and the bride towards the west. Upon the bridal throne there is now placed for the bride to stand upon a basket filled with grain, and for the groom the beam of a loom. The screen is now taken away, and the priest, a Dāsari, asks

[361]whether the elders, the Māla people generally, and the village as a whole, are in favour of the marriage. This he asks three times. Probably, in former times, it was possible to stop a marriage at this point, but now it is never done, and the marriage is practically binding after Pedda Tāmbūlam has been gone through. Indeed, in hard times, if the bride is of marriageable age, the couple will live together as man and wife, putting off the final ceremony until times are better. The groom now salutes the priest, the bride places her foot on the weaving beam, and the groom places his foot upon that of the woman as a token of his present and continued lordship. After this, the bride also is invested with the kankanam. After the groom has worshipped the four quarters of heaven, the priest, who holds in his hands a brass vessel of milk, hands the golden marriage token to the groom, who ties it round the bride’s neck. This is the first time during the ceremony that either of them has looked on the other. Before the groom ties the knot, he must ask permission from the priest and people three times. The priest now dips a twig of the jivi tree (

Ficus Tsiela) into the milk, and hands it to the husband, who, crossing his hands over his wife’s head, allows some of the drops to fall upon her. The wife then does the same to the husband. After this, the rice which the bride brought with her in her lap is used in a similar blessing. The priest, holding in his hand a gold jewel, now takes the hands of the two in his, and repeats several passages (charms). Whoever wishes may now shower the pair with rice, and, after that is done, the priest publicly announces them to be man and wife. But the ceremonies are not yet ended. The newly-married pair, and all the assembled party, now proceed to the village shrine to